This page of Lanting Xu (Preface of the Orchid Pavilion)《蘭亭序》by Wang Xizhi (王羲之) consists of :

- Origins of the Preface,

- The occasion – Xiu xi (修禊),

- Translation

- Appreciation of the calligraphy

- A Painting related to Lanting Xu

- Another famous copy of Lantang Xu called Dìng wǔ běn (定武本)

- Comparative studies of imitation copies of Lanting Xu

- Controversies over the authenticity of Lanting Xu

- A Visit to Zhishan Garden (至善園)

1. Origins of the Preface:

The Lanting Xu (Preface of the Orchid Pavilion)《蘭亭序》or Lanting ji Xu 《蘭亭集序》is a famous work of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi (王羲之) (301 CE to 363 CE), composed in the 353 CE. Written in elegant semi-cursive script and underpinned by deep philosophical thinking, it is among the best known and often copied pieces of calligraphy in Chinese history and also a famous piece of Chinese literature. It is revered as the best running calligraphy (天下第一行書). Wang Xizhi is respected as Shu Sheng (書聖), ‘Sage of Calligraphy’ or ‘Super Master of Calligraphy’.

Lanting Xu contains 28 vertical lines and 324 characters.

According to legend, the original copy was passed down to successive generations in the Wang family in secrecy until the monk Zhi Yong (智永), dying without an heir, left it to the care of a disciple monk, Bian Cai (辯才). Emperor Tai Zong of Tang Dynasty (唐太宗) (599 CE to 649 CE) heard about this masterpiece. He sent messengers on three occasions to retrieve the text, but each time Bian Cai responded that it had been lost. Finally Tai Zong dispatched Xiao Yi (蕭翼) who, disguised as a wandering scholar, gradually gained the confidence of Bian Cai and persuaded him to show him the Preface of the Orchid Pavilion. Thereupon, Xiao Yi seized the work, revealed his identity, and took it back to Tai Zong. Tai Zong loved this masterpiece very much and ordered the top calligraphers such as Yú Shì-nán (虞世南), Chǔ Suì-liáng (褚遂良), Féng Chéng-sù (馮承素), and Ouyáng Xún (歐陽詢) to trace, copy, and engrave into stone for posterity. Tai Zong treasured the work so much that he had the original interred in his tomb, Zhao lin (昭陵), after his death. The authentic Lanting Xu has not been seen since then.

2. The occasion – Xiu xi (修禊):

Xiū xì (修禊) was a purification ritual to ward off the evil spirit and bring good fortune. It took place on the third day of the Third Lunar Month. Wang Xizhi (王羲之) composed and wrote this masterpiece on this day of purification ritual in 353 CE (1662 years ago). This ritual is no longer celebrated widely in China today but the event is still commemorated in Shaoxing (紹興), the original place. Scholars still practise it in Lanting every year. Japanese scholars and elites also commemorate the event on that day, in particular in 60th year anniversaries when the lunar year coincides with the year 癸丑 1913, 1973, 2033. In 1973 there was a great exhibition in Japan of everything related to Lanting, and a good catalogue was published.

In 2015, this day falls on 21 April (Tuesday).

3. Translation:

永和九年,歲在癸丑,暮春之初,會於會稽山陰之蘭亭,脩稧事也。

In the ninth year of the Yǒng-hé (353 CE), at the beginning of the third moon, on this late spring day we gathered at the Orchid Pavilion in the Guì-jī, Shanyin (present-day Shaoxing (紹興) of Zhejiang (浙江) province), for the purification ritual.

羣賢畢至,少長咸集。

All the literati have finally arrived. Young and old ones have come together.

此地有崇山峻領(嶺),茂林脩竹;又有清流激湍,映帶左右,引以為流觴曲水,列坐其次。

Overlooking us are lofty mountains and steep peaks. Around us are dense wood and slender bamboos, as well as limpid swift stream flowing around which reflected the sunlight as it flowed past either side of the pavilion. Taking advantage of this, we sit by the stream drinking from wine cups which float gently on the water.

雖無絲竹管弦之盛,一觴一詠,亦足以暢敘幽情。

Despite of the absence of the grandeur of musical accompaniment, drinking wine and chanting poems give us delight and allow us to exchange our deep feelings.

是日也,天朗氣清,惠風和暢。

As for this day, the sky is bright, the air is fresh and the breeze is mild and bracing.

仰觀宇宙之大,俯察品類之盛。

Looking up, we admire the beauty of the sky and wonder at the immensity of the universe. Looking around us, we see the myriad variety and wonder at their extraordinary diversity.

所以遊目騁懷,足以極視聽之娛,信可樂也。

Stretching our sights and freeing our minds, we can stretch the pleasures of our senses (of sight and sound) to the limit. This is really delighting!

夫人之相與,俯仰一世,或取諸懷抱,悟言一室之內;

People gather together, in a blink, life passes by. Some find relief in freeing their thought and hopes and discuss their ambitions in (the quiet atmosphere of) a study or closet.

或因寄所託,放浪形骸之外。

Some free themselves from the shackles of their body in their search for spiritual refuge.

雖趣(取/趨)舍萬殊,靜躁不同,當其欣於所遇,暫得於己,怏然自足,不知老之將至;

Despite the interests and moods are widely different, tranquillity and recklessness are not the same, we all share one thing: whatever circumstances we meet, we can get some fleeting happiness, and there for just a moment, in self-satisfaction, making us hardly realize how fast we grow old.

及其所之既倦,情隨事遷,感慨係之矣。

When we become tired of our desires and the circumstances changes, disappointment and grief will come.

向之所欣,俛仰之間,已為陳跡,猶不能不以之興懷;

As for all that happiness, in a blink of time, it is already a past tantalizing memory. We cannot help but lament and act in accordance with our emotions.

況脩短隨化,終期於盡。古人云:「死生亦大矣。」豈不痛哉!

Whether life is long or short is up to destiny, but in the end return to nothingness. The ancients said, ‘Birth and death are big events.’ How could it not be agonizing?

每攬(覽)昔人興感之由,若合一契,未嘗不臨文嗟悼,不能喻之於懷。

And look at the cause of sentiment of the ancients, it shows the same origin. We can hardly not mourn before their scripts although our feelings cannot be verbalized.

固知一死生為虛誕,齊彭殤為妄作。

Of one thing I am quite sure: it is foolish to believe that life and death are one, or that long-life can be equated with early death.

後之視今,亦猶今之視昔,悲夫!

The future generations will look upon us just like we look upon the past. How sad!

故列敘時人,錄其所述,雖世殊事異,所以興懷,其致一也。

So we recorded the people here and their works (poems). Even though time and circumstance will change, the cause for their feelings and moods remain the same.

後之攬(覽)者,亦將有感於斯文。

When people look back on us in the future, they will be moved by this prose.

(English translation done after TC Lai, Monica Lai, Liu Yi Ru and a contributor for Wikipedia.)

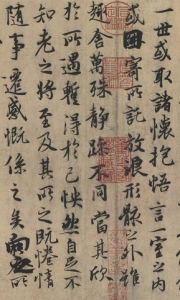

4. Appreciation of the calligraphy:

When Wang wrote the Preface, he was at high spirit after drinking wine with his good friends. There are traces of crossing out and additions. The first 3 lines of this masterpiece show clear regular script strokes. Then brush movement gradually becomes free flowing. The 8th – 11th line (see extract below) forms a beautiful rhythm. From the 12th lines onwards (see extract below) are the best, with the brush movement significantly turns faster in more casual style and takes natural and flowing style of writing, thereby leading to infinite reverie. The entire piece is free and unconstrained with full flavour, demonstrating Wang’s vigorous, robust and flowing running scripts.

It was said that Wang wanted to improve on the writing the next day and copied this work several times. However, he found the original writing was the best.

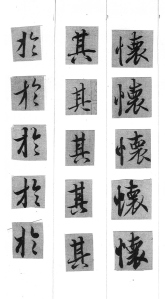

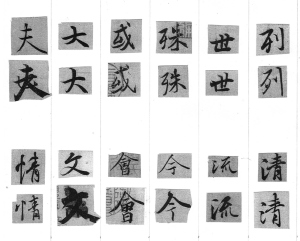

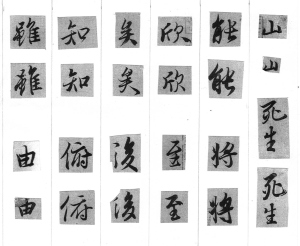

Wang’s calligraphy is always fresh and innovative. Each and every stroke of his writing has its own form and postures. Some words appear a number of times in Lanting Xu. The following pictures clearly demonstrate that each word is written differently.

Of the 324 words in Lanting Xu, the word zhi (之) appears 21 times.

The words yǐ 以, suǒ 所, yī 一, and bù 不 each appears 7 times.

The words yú 於, qí 其, and huái 懷 each appears 5 times.

The words yě 也, yì 亦, rén 人, and wèi 為 each appears 4 times.

The words zú 足, yang 仰, shì 視, gǎn 感, xìng 興, shì 事, and yǒu 有 each appears 3 times.

The words fū 夫, dà 大, huò 或, shū 殊, shì 世, liè 列, qíng 情, wén 文, hui 會, jīn 今, liú 流 and qīng 清 each appears 2 times.

Similarly, the words suī 雖, zhī 知, yǐ 矣, xīn 欣, néng 能, shān 山, yóu 由, fǔ 俯, hòu 後, zhì 至, and jiāng 將 and sǐ shēng 死生 each also appears 2 times.

5. A Painting related to Lanting Xu

The above is a painting of the gathering by an anonymous artist in the late Ming Dynasty. It shows guests seated along the banks of a small stream. Servants float wine-cups placed on leaves down the stream. When a cup stopped in front of a person, that person was expected to compose a poem, and if he failed, to drink several cups in forfeit.

6. Another famous copy of Lantang Xu called Dìng wǔ běn 定武本

It is believed that this is a copy version by Ouyáng Xún (歐陽詢). It was then engraved onto a piece of polished smooth stone for posterity. From the stone numerous rubbing copies were made. This is one of the rare and finest copies survived. The red seals are the seals of the collectors who once owned this fine copy. This copy is Wú Bǐng běn (version) (吳炳本) of Dìng wǔ běn and is kept in the Tokyo National Museum.

‧

Besides Ding Wu Wú Bǐng běn (version) (吳炳本), there are other Ding Wu ben such as Wang Yan ben (王沇本). Please click the following link to view a comparative study of three different versions of Ding Wu ben.

7. Comparative studies of 4 imitation copies of Lanting Xu

The first column on the right is Yu Shinan’s copy (虞世南臨本) (蘭亭八柱第一本)

The second column is Chu Suiliang’s copy (褚遂良臨本) (蘭亭八柱第二本)

The third column is Feng Chengsu’s copy (馮承素臨本) (蘭亭八柱第三本)

The fourth column is the Dingwu stone inscription copy (定武石刻本).

The whole piece contains 28 (vertical) lines. The photocopies of the four copies were cut and put together onto 28 pages. Each page shows only one line of the piece.

For the other 26 pages, please click the following link:

8. Controversies over the authenticity of Lanting Xu

There has been a great controversy about the authorship of Lanting Xu. Some scholars suggested that it was created two to three hundred years after Wang Xizhi passed away. Li Wen-tian (李文田), a scholar of the late Qing dynasty and many other people raised these queries. Some scholars even suggested that Zhi Yong (智永) might be the writer of Lanting Xu and he made up the whole story. The reasons for this speculation are :

First, the calligraphy of Wang Xizhi was fresh, elegant and innovative which is very different to the style of his contemporaries at that period. Two in-tomb epitaphs (墓誌銘) of the Eastern Jin were unearthed around 1964 and 1965. One of them was dedicated to Wang Xingzhi (a cousin of Wang Xizhi) and his wife (王興之夫婦墓志) and the other one was an epitaph to Xiè Sāi (謝鰓墓志). The characters of the epitaphs are square (方筆) in the style of Han clerical scripts (漢隸韻味). It was difficult to believe that Wang had abandoned the remnants of this clerical style and attained an elegant and fluidly (流暢) style. Guo Mo-ruo (郭沫若), a well-known modern historian and scholar, has claimed that the discovery of the two epitaphs confirm Li Wen-tian’s speculations.

The counter-argument is that Lanting Xu was written on paper in a relaxed manner and it should be different from the formal writings engraved onto stone to commemorate deceased persons.

Further, in 1909, wooden slips (木簡) and paper scraps (殘紙) of the calligraphy of the Wei (魏) and Jin (晉) Dynasties were unearthed in the lost city of Loulan (樓蘭) in the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert (塔克拉瑪幹沙漠) of Xinjiang (新彊). Among those are the letters of Lǐ Bǎi-wén (李柏文書) dated 307 CE, a few decades earlier than the time Lanting Xu was supposed to have been written. The calligraphy was running scripts in an elegant and fluidly (流暢) style. This indicates that running scripts can be common at the time of Jin.

Secondly, in Shi Shuo Xin Yu (世說新語), compiled and edited by Liu Yi-qing (劉義慶) (403 – 444) there is a passage called Lín Hé Xù (臨河序) and the text was identical to the first part of Lanting Xu with the exception of the last part in brown. The words in brown are not in Lanting Xu.

永和九年,歲在癸丑,暮春之初,會於會稽山陰之蘭亭,修禊事也。群賢畢至,少長咸集。此地有崇山峻嶺,茂林修竹,又有清流急湍,映帶左右。引以為流觴曲水,列坐其次。是日也,天朗氣清,惠風和暢,娛目騁懷,信可樂也。雖無絲竹管弦之盛,一觴一詠亦足以暢敘幽情矣。故列敘時人,錄其所述。右將軍司馬太原孫丞公等二十六人,賦詩如左。前餘姚令會稽謝勝等十五人,不能賦詩,罰酒各三鬥。

This passage was shorter and the extra text about philosophical thinking was not present. This led to scholars’ suspicion that Lanting Xu was not authentic because the this extra text could have been faked by people in later years.

Guo Mo-ruo further argued that the sentence 況脩短隨化,終期於盡 (whether life is long or short is up to destiny, but in the end return to nothingness) is a Buddhist way of thinking. Zhi Yong (智永) was a Buddhist monk. Lanting Xu might have been created by him.

The counter-argument is perhaps the shorter version recorded in Shi Shuo Xin Yu is an abridged version of the original Lanting Xu.

No matter who was the writer of Lanting Xu which survived today, it is still revered as the best running calligraphy (天下第一行書). Wang Xizhi is still the Shu Sheng (書聖).

9. A Visit to Zhishan Garden (至善園)

Zhishan Garden (至善園) at the National Palace Museum in Taipei is a recreation of traditional Chinese landscaping, bringing back the scenery that has inspired many of the ancient Chinese poets and scholars. Inside there is a replica of Lanting, Sōng Fēng Gé (松風閣), etc.

Acknowledgments :

I would like to thank Mr KC Wong for his continued support and guidance.

I also like to thank Professor P Lam for his kind advice and guidance.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor CHAN Yiu Nam (陳耀南教授) for teaching me Chinese Literature. Both of us are now living in Sydney.

Further readings / viewing :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w1rGoIYx6i4 (殷瑗小聚》中國美術史–蘭亭集序 (蔣勳) ( highly recommended)

http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/calligraphy-wang-xizhi-orchid.php

http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/calligraphy-wang-xizhi-orchid.php (with images of 2 fine paintings depicting the gathering of Lanting by Wen Zhengming (文徵明) and Zeng Jing (曾鲸)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lantingji_Xu (excellent English translation)

http://baike.baidu.com/view/590076.htm (a Chinese webpage on ‘purification ritual’修禊)

胡俊明 (2002) 名家大手筆《蘭亭集》序 商務印書館(香港) 有限公司 ISBN 962 07 4399 7 (highly recommended)

Lai TC & Lai M (1979) Rhapsodic Essays from the Chinese Kelly & Walsh Ltd. Hong Kong

掃葉山房主人 (2014) 再談《蘭亭序》真偽 星島周刊 Sing Tao Weekly (Australian Edition) 第 737 期 13/12/2014

掃葉山房主人 (2014) 王羲之功在變古通今 星島周刊 Sing Tao Weekly (Australian Edition) 第 738 期 20/12/2014

掃葉山房主人 (2014) 說《神龍本》蘭亭 星島周刊 Sing Tao Weekly (Australian Edition) 第 739 期 27/12/2014

陳耀南 (1991) 古文今讀: 初編 (p87 to p99) The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Wang Xinyu (2012) Classics Appreciation of Chinese Visual Arts – Calligraphy, The Yellow River Publishing & Media Group Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-7-227-05114-5/J.348

Ouyang Z and Wen C.F. (2008) Chinese Calligraphy, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12107-0

Hi Patrick, just wondering if you have an English translation of the Lo Shen Fu- Goddess of the Lo River, calligraphy done by Zhao Meng Fu.

I am starting to copy it but need a good translation and if you have any feedback that would be so helpful.

Hope all is well,

Kind regards,

GARRY.

LikeLike

Dear Garry, thank you very much for your message. For the time being, I have only found this version. I hope it can help you a bit.

曹植 《洛神赋》

黄初三年,余朝京师,还济洛川。古人有言,斯水之神,名曰宓妃。感宋玉对楚王神女之事,遂作斯赋。其辞曰:

余从京域,言归东藩。背伊阙,越轘辕,经通谷,陵景山。日既西倾,车殆马烦。尔乃税驾乎蘅皋,秣驷乎芝田,容与乎阳林,流眄乎洛川。于是精移神骇,忽焉思散。俯则末察,仰以殊观,睹一丽人,于岩之畔。乃援御者而告之曰:“尔有觌于彼者乎?彼何人斯?若此之艳也!”御者对曰:“臣闻河洛之神,名曰宓妃。然则君王所见,无乃日乎?其状若何?臣愿闻之。”

余告之曰:“其形也,翩若惊鸿,婉若游龙。荣曜秋菊,华茂春松。仿佛兮若轻云之蔽月,飘飘兮若流风之回雪。远而望之,皎若太阳升朝霞;迫而察之,灼若芙蕖出渌波。襛纤得衷,修短合度。肩若削成,腰如约素。延颈秀项,皓质呈露。芳泽无加,铅华弗御。云髻峨峨,修眉联娟。丹唇外朗,皓齿内鲜,明眸善睐,靥辅承权。瑰姿艳逸,仪静体闲。柔情绰态,媚于语言。奇服旷世,骨像应图。披罗衣之璀粲兮,珥瑶碧之华琚。戴金翠之首饰,缀明珠以耀躯。践远游之文履,曳雾绡之轻裾。微幽兰之芳蔼兮,步踟蹰于山隅。于是忽焉纵体,以遨以嬉。左倚采旄,右荫桂旗。壤皓腕于神浒兮,采湍濑之玄芝。

余情悦其淑美兮,心振荡而不怡。无良媒以接欢兮,托微波而通辞。愿诚素之先达兮,解玉佩以要之。嗟佳人之信修,羌习礼而明诗。抗琼珶以和余兮,指潜渊而为期。执眷眷之款实兮,惧斯灵之我欺。感交甫之弃言兮,怅犹豫而狐疑。收和颜而静志兮,申礼防以自持。

The Goddess of the Luo

Cao Zhi

In the third year of the Huangchu (1) era, I attended court at the capital and then crossed the Luo River (2) to begin my journey home. Men in olden times used to say that the goddess of the river is named Fufei. Inspired by the example of Song Yu, who described a goddess to the king of Chu, I eventually composed a fu which read:

Leaving the capital

To return to my fief in the east,

Yi Barrier at my back,

Up over Huanyuan,

Passing through Tong Valley,

Crossing Mount Jing;

The sun had already dipped in the west,

The carriage unsteady, the horses fatigued,

And so I halted my rig in the spikenard marshes,

Grazed my team of our at Lichen Fields (3),

Idling a while by Willow Wood (4),

Letting my eyes wander over the Luo.

Then my mood seemed to change, my spirit grew restless;

Suddenly my thoughts had scattered.

I looked down, hardly noticing what was there,

Looked up to see a different sight,

To spy a lovely lady by the slopes of the riverbank.

I took hold of the coachman’s arm and asked: “Can you see her? Who could she be – a woman so beautiful!”

The coachmen replied: “I have heard of the goddess of the River Luo, Whose name is Fufei. What you see, my prince — is it not she? But what does she look like? I beg you to tell me!”

And I answered:

Her body soars lightly like a startled swan,

Gracefully, like a dragon in flight,

In splendor brighter than the autumn chrysanthemum,

In bloom more flourishing than the pine in spring;

Dim as the moon mantled in filmy clouds,

Restless as snow whirled by the driving wind.

Gaze far off from a distance;

She sparkles like the sun rising from morning mists;

Press closer to examine:

She flames like the lotus flower topping the green wave.

In her a balance is struck between plump and frail.

A measured accord between diminutive and tall,

With shoulders shaped as if by carving,

Waist narrow as though bound with white cords;

At her slim throat and curving neck

The pale flesh lies open to view,

No scented ointments overlaying it,

No coat of leaden powder applied.

Cloud-bank coiffure rising steeply,

Long eyebrows delicately arched,

Red lips that shed their light abroad,

White teeth gleaming within,

Bright eyes skilled at glances,

A dimple to round off the base of the cheek —

Her rare form wonderfully enchanting,

Her manner quiet, her pose demure.

Gentle hearted, broad of mind (5),

She entrances with every word she speaks;

Her robes are of a strangeness seldom seen,

Her face and figure live up to her paintings.

Wrapped in the soft rustle of a silken garments,

She decks herself with flowery earrings of jasper and jade,

Gold and kingfisher hairpins adorning her head,

Strings of bright pearls to make her body shine.

She treads in figured slippers fashioned for distant wandering,

Airy trains of mistlike gauze in tow,

Dimmed by the odorous haze of unseen orchids,

Pacing uncertainly beside the corner of the hill.

Then suddenly she puts on a freer air,

Ready for rambling, for pleasant diversion.

To the left planting her colored pennants,

To the right spreading the shade of cassia flags,

She dips pale wrists into the holy river’s brink,

Plucks dark iris from the rippling shallows.

My fancy is charmed by her modest beauty,

But my heart, uneasy, stirs with distress:

Without a skilled go-between to join us in bliss,

I must trust these little waves to bear my message.

Desiring that my sincerity first of all be known,

I undo a girdle-jade to offer as pledge.

Ah, the pure trust of that lovely lady,

Trained in ritual, acquainted with Odes (6);

She holds up a garnet stone to match my gift,

Pointing down into the depths to show where we should meet.

Clinging to a lover’s passionate faith,

Yet I fear that this spirit may deceive me;

Warned by tales of how Jiaofu (7) was abandoned,

I pause, uncertain and despairing;

Then, stilling such thoughts, I turn a gentler face toward her,

Signaling that for my part I abide by the rules of ritual.

Notes:

(1) the Huangchu: i.e. 222 A.D.

(2) the Luo River: In Henan Province, so are Tong Valley and Mount Jing.

(3) Grazed my team of four at Lichen Field: Orig. — Grazed my horse on a fragrant grass field.

(4) Willow Wood: Name of a place.

(5) broad of mind: Orig. — deportment calm.

(6) with the Odes: Orig. — with poetry.

(7) Jiaofu: A character in a fairy tale who is abandoned by a goddess.

Please give me your email address so that Ican send information to you directly. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you Patrick for the Translation, very much appreciated.

Kind regard,

Garry.

LikeLike

ขอบคุณมาก

LikeLike

Hi Patrick and thank you for sharing your wonderful knowledge and skills and just want to let you know I am benefiting so much from your site.

I have been reading about the Lan Ting and have begun to do some tracing of the text as I am a novice and wonder if I could email you a sample of what I have been doing?

Kind regards,

Garry.

LikeLike

Dear Garry, Thank you very much for your kind support and encouragement. You are most welcome to share your amazing work with me. At the moment I in Hong Kong and I will be back to Sydney after 10 days. Kind regards, Patrick

LikeLike

Patrick,

May I use your image of the Preface Orchid Pavilion in my forthcoming book on Chinese history?

Thank you.

Michael Stone

Seton Hall University

michael.stone@shu.edu

LikeLike

Dear Michael,

Please feel free to use any images or photos created by me in all my web-pages for educational purposes. However, some of the images are from many different sources which I may not be able to trace.

Kind regards,

Patrick

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are a very generous scholar, Patrick. I will be linking to your posts when I teach Chinese art history this fall. I’m afraid the time zone may make it difficult, but it would be wonderful to “bring” you to my class via Skype, Oovoo, Facetime, Google, or whatever type of format you like. Would you be interested? My class meets 12:45-2:05, but we could hold a special, earlier session?

Best and thank you for your posts.

Lisa

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Professor Langlois, Thank you very much for giving me an opportunity to be involved in your lectures. Because of time difference between New York and Sydney, Australia, it will be a bit difficult for me to come to your ‘class’ through Skype, Facetime, etc. I will be more than happy to get involved through emails. Promoting Chinese fine art has always been my passion. Kind regards, Patrick

LikeLiked by 1 person

分析非常好,多谢! Thank you for sharing more of this great work with a western audience.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you very much for your kind support and encouragement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your work! I am an art historian specializing in Japanese art, but I also teach Chinese art and of course some Japanese artists treated these Chinese subjects as well. Your posts are very useful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

多谢蕭老師,這是不可多得的資料。自小知道王羲之是書聖,寫下傳世經典的蘭亭序,但直至現在才明白背後的歷史。蕭老師曾說過眼睛比手學得快,所以我們動手前要先學欣賞,很感激老師為我們分析蘭亭序,教會我們欣賞王羲之的書法。

LikeLiked by 1 person

The rich source of research material on Lanting Xu made us aware of the powerful, grandeur and diversity of the brushwork on Chinese Calligraphy.

Thanks for your generous contribution and incredible efforts on all your web pages.

LikeLiked by 2 people